- Home

- Anne Schraff

No Fear Page 4

No Fear Read online

Page 4

“Naomi,” Ernesto admitted, “I talked a little bit to Manny. He’s hanging with real bad dudes, but I don’t think he’s one of them yet. He said he’d seen you and me walking together from school. He wanted to know if you were my girlfriend. Manny looks bad, skinny and shaky, like he’s doing pills. But, Naomi, he asked me to say ‘Hi’ to you.”

“Did he really say that?” Naomi asked, her beautiful violet eyes widening.

“Yeah, he did,” Ernesto affirmed. “He hasn’t forgotten you.”

“I wish. .. I wish there was something I could do to help him,” Naomi said wistfully. “But if he came near the house, my dad would call the police. Mom is really hurting because she doesn’t have any contact with Manny or Orlando. Her heart is breaking.”

“Naomi,” Ernesto objected, “it doesn’t seem fair that your father forbids a mother to see her own boys. I mean, I know he’s your father and you respect him, Naomi. But it’s just not fair.”

“About three years ago,” Naomi explained, “they had this really horrible fight, my father and Orlando. I wasn’t even home. I was glad for that. I was staying with a girlfriend. Dad and Orlando started fighting, and Orlando hit Dad. He knocked him down. I mean, that was so awful. I love both my brothers, even now, but Orlando had no right to hit his father. Can you imagine hitting your own father? Dad threw all his stuff out into the front yard. He changed the locks on the doors. He told Orlando he can’t ever come back to the house because of what he did. And Mom and I, we haven’t seen him in three years.”

“It must be hard on your mom,” Ernesto commented.

Naomi nodded. She seemed about to say more, but her father came outside again. He’d drunk his third or fourth can of beer. “You comin’ in to dinner, Naomi?” he hollered. “Your mother has put the slop on the table. It’s even worse when it’s cold.”

“See you, Ernie,” Naomi said quickly, turning and hurrying in the house.

CHAPTER FOUR

Ernesto jogged to the pizzeria to do his shift. The barrio looked so peaceful this time of day, at dusk. Kids were riding their skateboards, twisting and turning, and coming down with amazing agility. The skateboards clattered, and the kids screamed with laughter. Guys were mowing their lawns, and you could begin to smell the aromas of cooking dinners. Ernesto looked at the skateboarders—boys, eleven or twelve, maybe a little older. They were just kids. They loved baseball and football. Some of them were already into rock and rap. They formed innocent little gangs that were about fun and games.

But in a few years some of them would turn into guys like Condor and Coyote. The street was like a nightmare scenario, an evil spell cast over the young. It was like a deadly disease that struck boys of a certain age, sending them to prison or an early grave. On some of their grave markers, bewildered parents would call them “good,” “precious,” “sweet.” They would never quite understand what had happened to their children.

Ernesto knew that the key to avoiding prison and death was education. His father knew it too. Ernesto knew a lot of guys at Cesar Chavez High School who could someday be gangbangers. They saw bad dudes with flashy cars and thick wads of money, and they wanted that kind of life—easy money. The gangbangers were dropouts, and dropouts were heroes. Ernesto’s father was trying to push education on the students whether they wanted it or not.

Luis Sandoval cared about the kids, especially the losers. His face lit up at the thought that he had kept Dom Reynosa and Carlos Negrete in school. That he’d brought Yvette back to school. Now they’d graduate. Some of them might go to college. The street couldn’t claim them anymore. They had soared above the dirty business that tried to suck out their hearts and souls before they could even become men and women.

That was why Luis Sandoval walked the streets of the barrio, looking for kids to rescue. He was a shepherd looking for lost sheep who could be led back to the fold before it was too late for them. And Ernesto now felt that a stinking chunk of concrete hurled through the window by a punk threatened to put an end to all that good work.

With a heavy heart, Ernesto went into the pizza shop to start work.

After school the next day, Ernesto and the other boys from Chavez’s track team gathered on the field. Coach Muñoz was going to make the decision on who would try out for which race and who would run in the relay. He would pick the fastest boy to anchor the relay team. Chavez was playing Wilson, and they had never beaten Wilson—or any other school. Gus Muñoz was in the twilight of his career, and the last time his track team had won anything was twelve years ago.

Julio Avila was primed for the tryouts. Even Jorge Aguilar and Eddie Gonzales looked pumped. Ernesto had been running relentlessly, and he was determined to be the anchor in the relay, running that all important last lap.

Julio Avila’s father watched from the sidelines, as he usually did. He was a downon-his-luck guy with only one claim to fame: his vibrant, amazingly athletic son. Julio wanted desperately to please his father. Julio had just one living parent, the grimy old man with the threadbare suit and sadness in his eyes. Julio was the only good thing that had ever happened to the old man, and the son was determined to make his father proud.

After all the boys had run their best, Coach Muñoz decided that both Ernesto and Julio would run in the hundred-yard dash. For the relay, Coach Muñoz announced, “We have two guys who are really good, but I’m going with Julio in the anchor spot.”

So Julio would get to run the last lap, leading the Cougars to victory. Ernesto wanted to run the last lap so badly he could taste it. But today Julio was the fastest on the team, and it was only right that he got the anchor spot. Seeing that old man out there in the stands jumping up and down for joy, Ernesto figured, would take some of the sting out of his disappointment.

Julio was grinning from ear to ear as he high-fived his father. Ernesto walked over to the Avilas and he said, “Okay, Julio, you took it away from me, but listen up. I’m gonna run the most amazing first lap you ever saw. By the time the third guy hands you the baton for the last lap, you won’t have much to do, ’cause the relay’ll be a cinch.”

Julio grinned. “Go for it, Ernie,” he urged.

Ernesto put out his hand and Julio took it. Mr. Avila looked at his son and then at Ernesto. “This is your friend, eh, Julio?” he asked.

“Yeah Dad, ” Julio said, “mi amigo.”

“Hey Julio,” Ernesto suggested, “since you got the anchor, we need to go over to Hortencia’s and celebrate. Come on, Mr. Avila, Julio.” Ernesto saw Naomi then, and he shouted to her. “Hey Naomi, we’re going over to Hortencia’s for tamales. Come on.” Naomi had come to watch the tryouts, and Ernesto wondered whether she’d come to watch him. He didn’t have any illusions about her being even close to dating him. But maybe she at least cared enough to watch him run.

Naomi came walking over, a smile on her face. “You guys were both awesome,” she complimented them. “I think for the first time ever, we’re gonna whip Wilson. Those Wolverines won’t have so much to howl about for a change. Coach Muñoz’ll be retiring soon, and it’d be so cool to send him off a winner.”

They all crossed the street to Horten-cia’s and took a booth. Hortencia seemed especially radiant these days, and Ernesto couldn’t help attributing her happiness to Oscar Perez. Dating a guy like that had to be exciting for her.

“You guys,” Hortencia announced, “Oscar is gonna come here with his trio on Sunday night. I’m opening the patio ’cause there’ll be tons of people. You gotta come.”

“Sure,” Ernesto agreed. “I’ll be here. I’ve never seen his trio.”

“Me too,” Naomi chimed in, looking at Ernesto. “If there’s room for me in the Volvo.”

Ernesto’s heart skipped a beat. “I think there’ll be room, Naomi,” he said, not wanting to show his excitement too much.

All the way home, Ernesto kept telling himself this would not be a date with Naomi. This would just be giving a friend a ride to the concert at Hortencia’s.

> When Ernesto got home, Katalina was playing in the front yard. She demanded, “Did you get the anchor in the relay race, Ernie?”

“No, but I get to run a lap, and I’ll show ’em,” Ernesto replied cheerfully.

“No fair!” Katalina said grumpily. “You shoulda got it.”

“It’s okay, Kat,” he consoled her.

He was glad to see the men working on installing the new picture window. It was double-paned and much more resistant to damage.

“It’s beautiful,” Mom declared, “and it’ll make the room warmer in winter and cooler in summer. And now we have a security system too. Did you see the sign out front? Anybody walks onto our property’ll trip a sensor.” Mom seemed happy and relieved after the scare they had.

On Sunday evening, Ernesto went to Naomi’s house to pick her up. The weather was clear and beautiful. Santa Ana winds had been blowing earlier in the day. Everything was sharp and vivid, including the moon and the stars.

“I wonder what Oscar’s trio is like,” Naomi wondered, as they headed for the tamale shop. “He’s so good, but the trio has got to make the music even more exciting.”

Quite a few cars were already parked at Hortencia’s when they arrived. Ernesto’s heart sank when he saw Clay Aguirre’s Mustang. But then he noticed Clay had a pretty girl with him, Mira Nuñez, also a junior. Ernesto hoped that was a sign that Clay had given up on getting Naomi back. Maybe he was hooking up with somebody else. Ernesto did feel a little sorry for Mira Nuñez, though.

The minute Ernesto and Naomi walked into the patio, Clay turned sharply and stared at them, ignoring Mira completely. That made Ernesto sick.

Naomi tried to act unconcerned. She focused on Oscar Perez as the handsome young man adjusted his equipment on the stage. The three men in the trio appeared. All seemed much younger than the thirty-something Perez, but all three were strikingly good-looking. They had thick, longish black hair, and they wore crisp white shirts and dark jeans.

“Ernie!” Naomi cried out with such intensity that Ernesto’s blood ran cold. He thought she’d been hurt or something.

“What? What’s the matter?” he demanded, turning toward her.

“That’s my brother!” Naomi gasped. “That’s Orlando! The one on the left! Oh Ernie!” Naomi was clutching Ernesto’s arm so tightly that her fingers were hurting him.

Ernesto looked up at the boy on the left. He could see Felix Martinez in the deep, dark, almost fierce eyes, the determined set to his mouth, the dark skin. Felix was much darker than his wife, just as Luis Sandoval was darker than Ernesto’s mother. But when the music started, the boy’s expression turned joyful, and a brilliant smile broke his dark face.

Tears streamed down Naomi’s face. Ernesto put his arms around her and pulled her gently and protectively against him. He didn’t care what Clay Aguirre might be thinking. “Ohhh Ernie,” Naomi whispered in a shaky voice. “I haven’t seen my brother in three years! He looks wonderful!”

Oscar Perez and his trio sang Mexican folk songs and popular American songs. To the delight of the young audience, they even did some rap. Ernesto noticed that Naomi didn’t take her eyes off her brother. In the middle of one of his solos, Orlando looked right at his sister and smiled. During the intermission, Orlando came over to where Naomi was sitting with her friends, and he reached out his arms. Naomi fled into them.

“Mi hermana!” Orlando said in an emotional voice, holding her at a distance from himself. “When I last saw you, you were a little girl. Now you are a beautiful woman!”

“Oh Orlando, I miss you so much,” Naomi told him. “Mama misses you. Every night she says a rosary for you and for Manny. I hear her in her room praying with the candles lit in the glass with Our Lady of Guadalupe on it.”

“How is Mama?” Orlando asked.

“She is. .. all right, Orlando,” Naomi replied.

“And Manny, do you see him?” Orlando asked.

“No,” Naomi answered.

“But he is okay, huh?” Orlando said.

Ernesto spoke up. “No, he’s not.”

Orlando looked from his sister to Ernesto. “Who is this boy, Naomi?” he asked.

“Ernesto Sandoval, Orlando.” Naomi made the introduction. “He’s a special friend of mine. His father teaches history at Chavez High. I have him. He’s a wonderful teacher.”

Orlando looked right at Ernesto. Something about his almost sinister stare reminded Ernesto of Felix Martinez. He was his father’s son in the anger that leaped quickly to his eyes. Ernesto could easily imagine why the two had clashed so bitterly.

“Why do you say my brother is not okay?” Orlando demanded. “Tell me what you know about him. I am very concerned. In the beginning we texted and talked, but then he had no phone. He vanished.”

“He hangs out on the street with gangbangers, real hardcore guys,” Ernesto explained. “I don’t think he’s one yet. He’s probably a gofer for them. But he looks bad. He looks like he doesn’t get enough to eat, and he’s dirty like he’s homeless.”

Orlando clamped his hand to his head and cursed. Then he asked, “After the classes are over tomorrow at your school, Ernesto, will you help me to find my brother? I must find him.”

“Yeah, sure,” Ernesto agreed. “Come to the school parking lot. You and Naomi can ride in my Volvo. I’m pretty sure I can find him. The gangbangers and the wannabes have their regular hangouts.” Then Ernesto remembered.

“I have to be at work by four,” he told Orlando. “Should I call and say I might be late?”

“Nah man,” Orlando replied, “you don’t have to do that for me. If it takes too long, we’ll try again. OK?”

“Cool,” Ernesto agreed. “But let’s hope we have enough time. I think I know where to look.”

After school the next day, Orlando was already waiting by the Volvo when Ernesto and Naomi walked up to it. They left the school, heading for the deli and the around-the-clock convenience store where guys were always hanging. They circled the block without seeing anybody. Then Ernesto spotted a gaunt figure checking out the dumpster in the back of the market.

“There he is,” Ernesto pointed. They’d found him right away.

“Pull over!” Orlando commanded. When Ernesto did, Orlando leaped from the car and sprinted toward his brother. Ernesto and Naomi followed.

Manny turned. He didn’t immediately recognize the big guy running toward him as his brother. Orlando had been a skinny kid the last time Manny saw him. The dude coming at him fast looked as though he weighed at least a hundred and seventy. Orlando had short hair before, and now it was long. Manny took off running.

“Manuel!” Orlando shouted as his younger brother fled. The younger boy continued running, but Orlando overtook him, grabbing his shoulders and turning him around. “Manny, it’s me! It’s Orlando.”

Manny looked shocked and a little frightened. He saw Naomi then, and the sight of her calmed him down. Naomi rushed to her brother and hugged him, ignoring how he looked and smelled. She was crying when they separated.

“Whatcha been doin’, man?” Orlando demanded, yelling in his brother’s face. “You had my cell number. You coulda called. How come you cut me off?”

Ernesto could see more and more of Felix Martinez in this angry young man. He was tough, almost brutal.

“You been hangin’ with creeps, homie. What’s wrong with you?” Orlando seemed as short on compassion as Felix Martinez. Then he grabbed his younger brother and hugged him. “Man, you could die out here. You’re like a skeleton, dude. You look sick. Come on, we’re goin’ to see somebody.”

“Who?” Manny gasped. “You ain’t takin’ me home are you? The old man’ll kill me.”

Finally Orlando laughed. It wasn’t a happy laugh. It was an angry, sneering laugh. “Man, he’d try to kill me too,” Orlando declared. “We’re gonna see the old man at the church. Padre Benito.”

Our Lady of Guadalupe Church was just a block away, a rather shabby-looking little frame building set cl

ose to the street. The pastor was Padre Benito, a man about fifty who looked older. When the four of them went into the tiny office, the old priest was sitting there. He wore a white shirt and shiny slacks that had seen better days. The people who attended Sunday Mass at this church did not put much into the collection plate.

“Well, I know you, Ernesto,” the priest said. “And Naomi, you come with your mama sometimes, but I don’t remember these other two.”

“I’m Orlando Martinez,” the brother replied, “and this is my brother, Manuel. Our parents, Felix and Linda, they belong to this church. I know my father doesn’t show up often, but my mother does.”

“Ahhh,” the priest sighed. “You used to serve the 7:30 mass. And Manuel, you served at 10:30. Such a long time ago.”

Manny said nothing. He hung his head. He hadn’t had a bath in a long time. He was shaggy and dirty, but he hadn’t cared until now. Now he felt ashamed.

“Padre,” Orlando continued, “he’s homeless. Our father threw us both out. I’ve made a good life in Los Angeles. I’m with the Oscar Perez trio. I can’t take Manny in now, but I will later. My brother needs a place to clean up, three squares a day until I can arrange something. He’s been hanging with the homeboys. I’m afraid pretty soon he’ll be in trouble. Can you find him a place where he can hang until I figure something out? I can’t just leave him on the street.”

The old priest nodded. “I’ll call Father Joe. He’s is a good man to call when you’re in a tight spot.”

Padre Benito got on the phone and chatted with somebody for a few minutes. He said there was a sale on potatoes and his car was loaded with a dozen bags. A nice lady at church had donated them for Father Joe. Then he talked about the boy who needed a place. He nodded and put down the phone.

“Manny,” Padre said quietly, “I’m going down now with the potatoes. You can ride along.”

Orlando Martinez threw an arm around his brother’s thin shoulders and told him softly, “Gonna be okay, mi hermano.”

Unbroken

Unbroken Wildflower

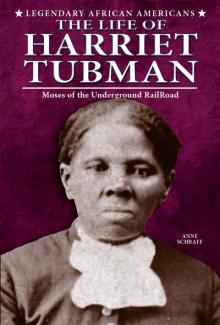

Wildflower The Life of Harriet Tubman

The Life of Harriet Tubman Like a Broken Doll

Like a Broken Doll Rosa Parks

Rosa Parks No Fear

No Fear Albert Einstien

Albert Einstien To Be a Man

To Be a Man The Life of Frederick Douglass

The Life of Frederick Douglass Someone to Love Me

Someone to Love Me A Matter of Trust

A Matter of Trust Until We Meet Again

Until We Meet Again If You Really Loved Me

If You Really Loved Me